The Farming Tax Was Never About Fixing the Public Finances — It Barely Covers One Day of Borrowing

With borrowing running at £163bn a year, the numbers show this tax was always economically irrelevant.

The government has softened its proposed inheritance tax on farmland — but it’s worth being clear upfront: this policy was never going to make a dent in the public finances, and it still won’t. The threshold has been raised from £1 million to £2.5 million ahead of the planned start date in April 2026, following months of protests and growing concern in rural constituencies.

The retreat was predictable — because the policy was built on a misunderstanding of both the public finances and how farm businesses actually operate.

🗣️ “Sensible Reform”… Then a Sudden Climbdown

The contrast between the Prime Minister’s firm stance and today’s policy shift has fuelled accusations that the government is “all over the place” on rural policy.

Just last week, Keir Starmer doubled down on the inheritance tax changes, explicitly defending them as a “sensible reform” and insisting the government would not change course — even as MPs confronted him with farmers’ fears about what the policy could mean for family farms.

Yet today, the government has more than doubled the tax-free threshold to £2.5m, in a move that amounts to a major climbdown and a tacit admission that the original plan was politically and practically unworkable. After months of arguing that the £1m cap was fair, the sudden shift leaves an impression of leadership that is reactive and inconsistent rather than guided by any clear “sensible” strategy.

💷 This Was Never a Serious Attempt to Fix the Public Finances

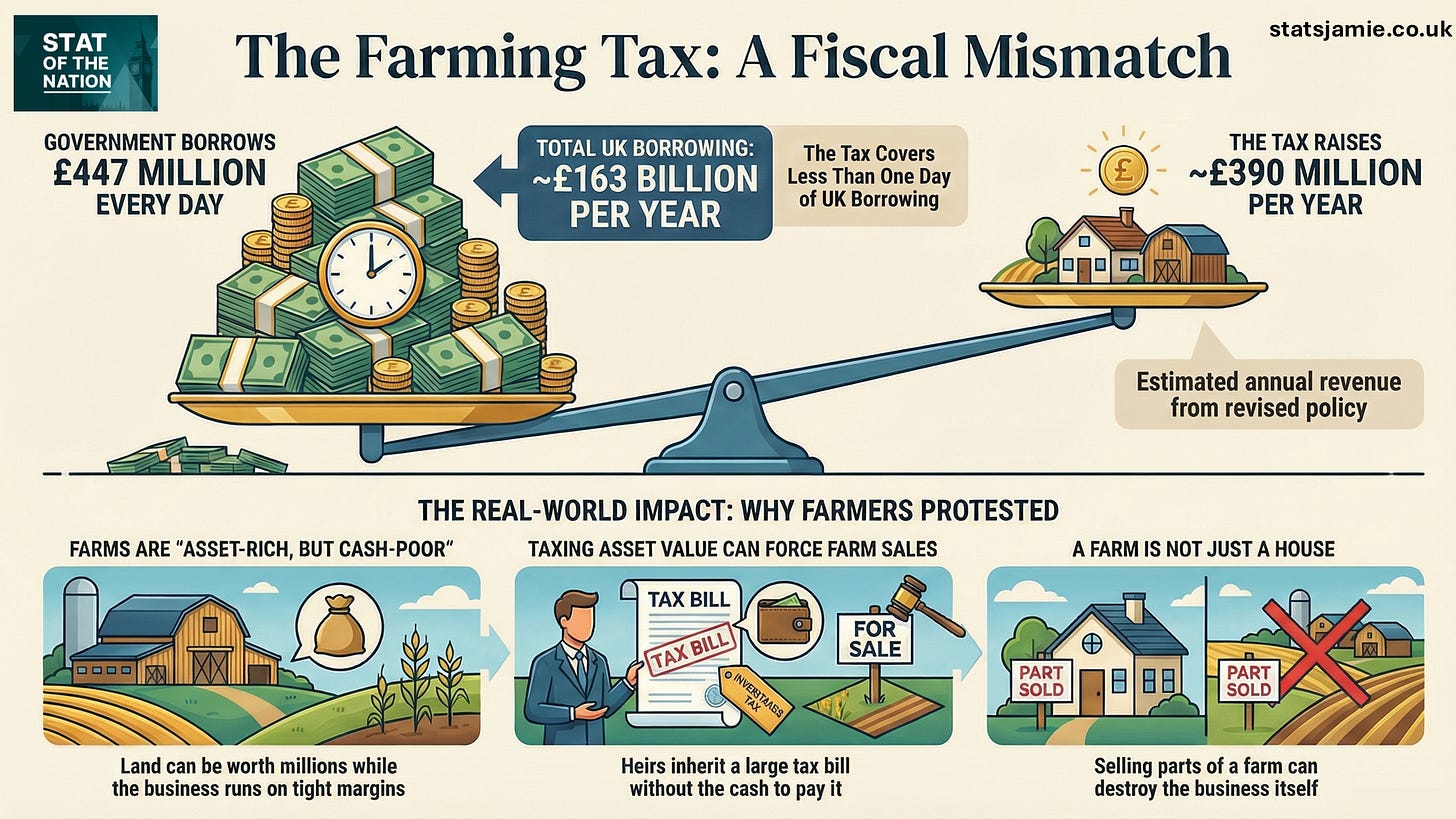

The original tax was expected to raise around £520 million a year. Reports suggest the U-turn will cost the Treasury roughly £130 million, implying the revised policy now raises around £390 million annually.

The maths makes the point almost immediately. The government is borrowing around £163 billion a year — roughly £447 million every single day. Even at its original estimate of £520 million a year, the farming tax would have covered just over one day of borrowing. After the U-turn, at around £390 million a year, it doesn’t even manage that.

That’s why this was never about fixing the public finances — it was political. Government can sign off spending decisions worth hundreds of millions with remarkable ease — but when it comes to raising money, every tax has real-world consequences. If you choose to raise a relatively small sum from a narrow group, you need to be honest about what you’re doing and what it will cause. In this case, the consequence is obvious: taxing inherited farmland based on asset values risks forcing sales and breaking up working farms that operate on tight, volatile margins.

🚜 Why the Tax Was So Unpopular

The backlash happened for a simple reason: farms are often asset-rich but cash-poor.

Government farm income data makes the point plainly: farming is volatile, and a significant share of farms don’t make a profit. So when ministers talk about “wealthy” farms, they’re often confusing paper value with cash reality. Land can be worth millions while the business runs on tight, uncertain margins — which is exactly why an inheritance tax based on asset values risks forcing sales.

In plain terms, you can inherit a high-value asset without inheriting the cash needed to pay a large tax bill tied to that asset.

🧾 Why Asset Taxes Force Sales

Inheritance taxes on assets create a basic cash-flow problem.

When a tax is charged on the value of an asset — such as farmland — the bill is due even if the person inheriting it has little or no cash. A farm can be worth millions on paper without producing anything close to that in income.

In practice, heirs often face a large bill without the money to pay it. The realistic options are to sell land, break up the farm, or take on heavy debt.

For family farms operating on tight and uncertain margins, that can threaten the viability of the business itself.

This is why farmers describe themselves as asset-rich but cash-poor — and why taxing inheritance on land value risks forcing sales rather than raising sustainable revenue.

🏠 “Why Should Farmers Be Different?”

Some will ask: Why should farmers be treated differently from anyone inheriting a valuable house? Inheritance tax can indeed force sales in any sector — if you inherit a £5 million home, you may have to sell it to pay the bill. The difference is that a family home is not a productive asset in the same way a working farm is. A farm is a trading business tied to land; selling chunks of it can permanently reduce output, break up the business, and in some cases end the farm altogether. In other words, the tax doesn’t just change ownership — it can change what the asset can do.

🎯 The Bigger Point

This episode reveals a deeper flaw in the process of creating tax policy.

The government picked a headline-grabbing tax with a tiny fiscal payoff, triggered a political firestorm, and still ended up with a policy that barely moves the dial on borrowing and debt.

When the state is borrowing £163 billion a year, arguing over roughly £390-520 million is not a fiscal strategy. It’s symbolism.

✅ Conclusion

This episode shows that the farming tax was never about fixing the public finances.

While it may have been presented as a considered policy, its tiny fiscal impact compared with the scale of government borrowing meant it was always more symbolic than substantive.

If the government is serious about repairing the public finances, it will need to confront spending, debt, and growth — not rely on politically costly taxes that barely register in the Treasury’s accounts.

✍️ Jamie Jenkins

Stats Jamie | Stats, Facts & Opinions

📢 Call to Action

If this helped cut through the noise, share it and subscribe for free — get the stats before the spin, straight to your inbox (no algorithms).

📚 If you found this useful, you might also want to read:

📲 Follow me here for more daily updates: