£163bn a Year Borrowed — Reeves’ Spending on the State Is Out of Control

Taxes are at record highs, yet borrowing is still rising — because the cost of running the state keeps growing.

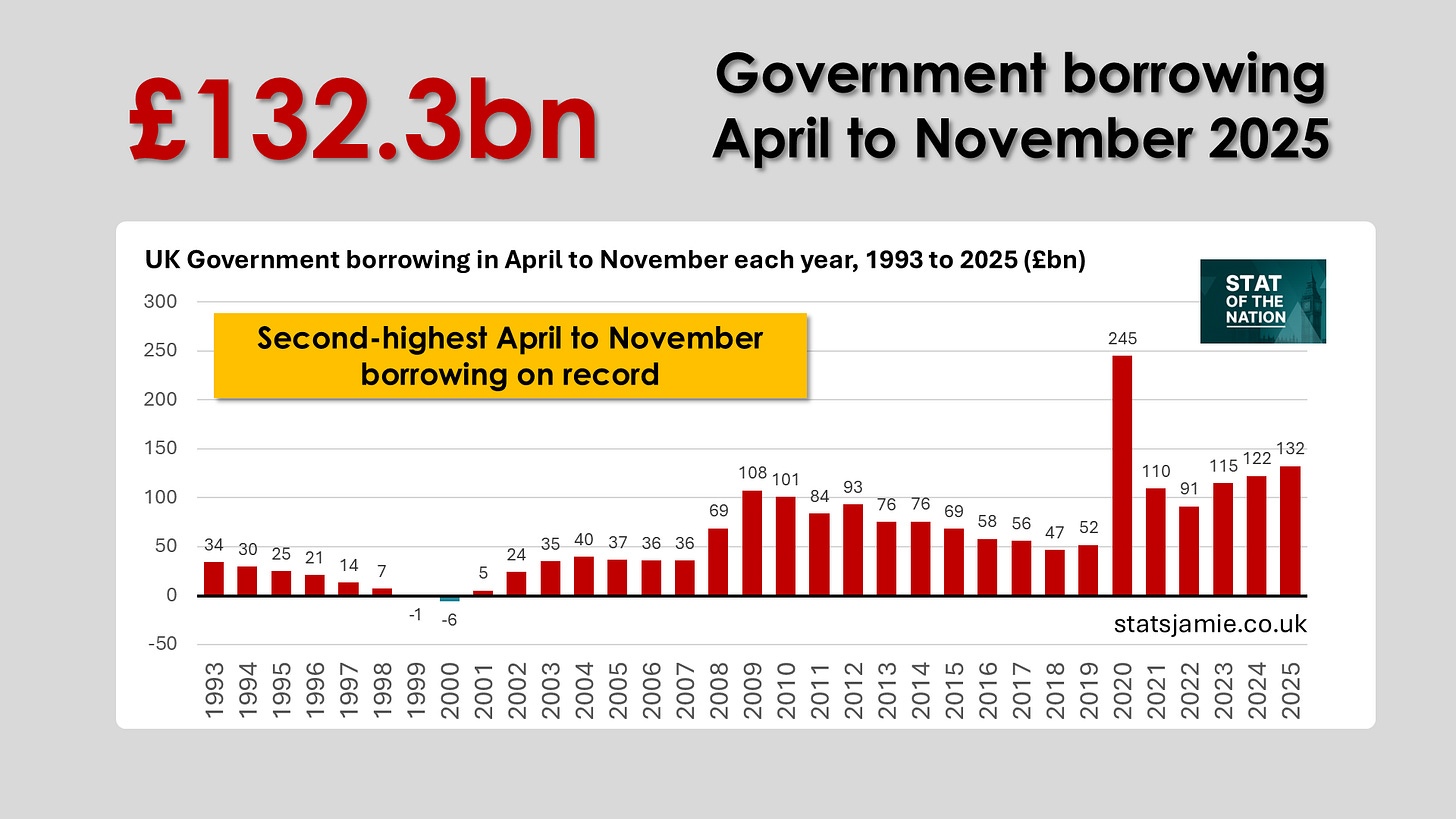

The latest public sector finances show that between April and November, the UK government borrowed £132.3 billion — the second-highest April–November total on record, beaten only by 2020, when borrowing surged during the Covid pandemic response. On a rolling 12-month basis, borrowing is now running at around £163 billion a year.

Outside that extraordinary period, the UK has never borrowed this much so early in a financial year.

This is not about monthly volatility or one-off shocks. It reflects a deeper, ongoing problem in the public finances — one that timing effects or seasonal quirks cannot explain away.

To understand what is really going on, we need to step back and look at where the government gets its money from, where it spends it, and how those two have been moving over time.

🧾 Where does the money come from — and where does it go?

Year-to-date figures are useful for context, but they don’t tell us how sustainable the public finances really are. For that, we need to look at a full 12 months of data, which smooths out seasonal effects and shows the underlying run-rate of the state.

So instead of focusing on individual months, the analysis below looks at the most recent 12-month period — December through to November — to answer two simple questions:

How much money is the government bringing in?

How much is it spending, and on what?

The difference between the two is borrowing.

💷 What the government brings in

Over the most recent 12 months, central government raised around £1.08 trillion in revenue.

That money mainly comes from three large tax buckets:

Taxes on income and wealth: ~£434bn

Dominated by income tax, alongside capital gains tax and corporation tax.Taxes on production: ~£355bn

Driven primarily by VAT, plus fuel, alcohol and tobacco duties.National Insurance contributions: ~£195bn

Paid by employees and employers — effectively a major jobs tax linked directly to payrolls.

Beyond those core streams, there are smaller contributions from other taxes, interest and dividends, and miscellaneous receipts.

Compared with the previous 12 months, total receipts are up by around £66 billion. That is a substantial increase — and it matters, because it immediately rules out one explanation.

This is not a revenue-starved state. The government is already taking well over a trillion pounds a year from households and businesses.

💸 What the government spends

Over the same 12-month period, central government spent about £1.09 trillion just on day-to-day activity, before major investment is even considered.

That day-to-day spending breaks down into three dominant areas:

Welfare and net social benefits: around £322 billion

Running government departments and public services: around £665 billion

Debt interest: around £98 billion

Debt interest alone now costs nearly £100 billion a year — money spent servicing past borrowing rather than delivering services today.

Once depreciation and capital investment are added, central government borrowing over the past 12 months comes to around £156 billion. Including local government and other public sector components takes total public sector borrowing to around £163 billion.

📈 Borrowing is getting worse, not better

What makes this picture more troubling is the direction of travel.

Compared with the previous 12-month period:

Tax receipts rose by around £66bn

Investment spending fell slightly

Yet borrowing increased

The reason is straightforward: recurrent spending is rising faster than revenue. Welfare costs, public sector pay and debt interest are all moving in the same direction — up.

Higher taxes have not stabilised the public finances because they have been outpaced by higher spending.

👥 The state is expanding while the private sector weakens

At the same time, the structure of the economy is shifting uncomfortably.

Recent labour-market data show:

Public sector employment and pay are continuing to rise

Private sector employment is weakening

That matters because the private sector ultimately funds the state. When the part of the economy that spends grows faster than the part that pays, the fiscal position becomes increasingly fragile.

Over time, this dynamic risks:

Slower growth in tax receipts

Higher welfare spending

And persistently higher borrowing

🏛️ Local government: pressure pushed down the system

The strain is not confined to Whitehall. Local government finances tell a similar story.

Over the most recent full year, councils raised around £238 billion in revenue but spent about £255 billion. Roughly £10 billion of borrowing went on capital investment, but around £7 billion was required simply to cover day-to-day costs.

The single biggest driver is adult social care — a legally mandated service facing rising demand and costs, with funding that has not kept pace. Borrowing has become the release valve.

National policy choices are pushing fiscal pressure down the system — and it all feeds back into headline borrowing.

🎯 Welfare is a choice, not an accident

Welfare spending is already rising automatically as growth slows and demographic pressures intensify. On top of that, the government has announced that the two-child limit will be removed from April 2026, locking in higher benefit spending in future.

There is no corresponding plan to reform the welfare system or offset the cost elsewhere. Choosing not to reform welfare is a choice — and it is a choice that bakes higher borrowing into the future.

🚫 Why tax rises won’t solve this

Faced with rising borrowing, governments have only two levers: raise taxes or control spending.

The government is already leaning hard on the tax lever. The recent Budget raises taxes by amounts rising to £26bn in 2029/30, driven by the freeze in personal tax thresholds and a host of smaller measures, and it takes the tax burden to an all-time high of 38% of GDP in 2030/31.

Yet even with receipts rising, borrowing is still running at around £160bn a year. Which brings us to the problem with the government’s current approach: at this scale, many of the headline “tax fixes” being discussed are simply too small to matter.

Take the inheritance tax changes affecting farmers. The policy is expected to raise around £500 million a year once fully in force. That is not a serious fiscal solution — it is a rounding error against a deficit of this size. In fact, it would take roughly 325 years of revenue from that tax to cover one year of borrowing at today’s run-rate.

This is the reality the government is trying to avoid. You do not fix a £160-billion-a-year deficit by squeezing ever smaller groups harder. If borrowing is going to come down, it will only happen by slowing the growth of the biggest spending lines — the day-to-day cost of running the state and the welfare system.

🧮 The unavoidable arithmetic

This is not a question of ideology. It is arithmetic.

When:

The tax take is already at record levels

Day-to-day spending absorbs almost all of it

Welfare and the cost of running the state continue to rise

And the private sector weakens

Borrowing will remain high — unless spending growth is brought under control.

Without a serious effort to curb the state's growth, Britain is heading toward permanently higher deficits and a steadily rising debt burden.

✍️ Jamie Jenkins

Stats Jamie | Stats, Facts & Opinions

📢 Call to Action

If this helped cut through the noise, share it and subscribe for free — get the stats before the spin, straight to your inbox (no algorithms).

📚 If you found this useful, you might also want to read:

📲 Follow me here for more daily updates: