Ed Miliband vs Winter: When Net Zero Meets Cold Reality

Cold snaps don’t care about targets — they test whether homes can stay warm.

Britain is in the middle of a winter cold snap. Temperatures are low, heating is running across the country, and energy demand is rising sharply. This is the point at which energy policy stops being abstract and becomes physical. People are not thinking about targets or timelines. They are thinking about staying warm.

The cold snap began with several days of relatively calm conditions and weak wind output before shifting into more volatile, stormy weather — a reminder that wind generation is inherently variable, not reliably available when demand is highest.

Right now, the system is responding in the only way it reliably can. Wind output can fall during still winter weather. At night, solar produces nothing at all. Demand does not fall. Heating stays on. The gap between what is needed and what weather-dependent generation can provide has to be filled immediately.

That gap is filled by gas.

❄️ When Demand Peaks, Reality Takes Over

Winter is when energy systems are judged. Not on average days, but during cold, still periods when demand surges, and there is no margin for error.

Heating demand does not rise gradually. It jumps. Millions of homes switch on at the same time, often during the coldest hours of the day and night. Around 80% of British homes still rely on a gas boiler, delivering instant heat at scale. That physical reality has not changed.

What has changed is policy. In November 2025, Ed Miliband confirmed a ban on new oil and gas exploration licences, locking in a decision to shrink domestic gas production in pursuit of the government’s net zero strategy, even as winter demand remains unchanged. The consequence is not the end of gas use — it is the end of British gas supply.

Miliband’s strategy is clear: remove gas and expand wind. Gas is treated not as a critical source of heat and stability, but as something to be eliminated outright. Wind is expected to do the heavy lifting instead. The problem is that energy systems do not respond to ambition — they respond to weather.

🌬️ Wind Droughts Are a Feature of Winter

Periods of low wind are not anomalies. They are a predictable feature of the weather patterns that bring cold snaps to the UK.

High-pressure systems bring freezing temperatures and still air. Wind generation drops just as demand rises. At night, solar disappears entirely. The system cannot wait for the weather to change.

When the wind isn’t blowing, and it’s dark, the grid turns to the only source capable of filling the gap instantly and at scale.

Gas.

📊 Last Winter Shows What Actually Happens

This is not hypothetical. It already happened last winter.

The government’s own Energy Trends report covering January to March 2025 shows that near-record low wind speeds led to a 13% drop in wind generation. As wind output fell, gas became the single largest source of electricity. The report is explicit: increased gas generation reflected low wind speeds and a drop in net electricity imports.

This was not a failure. It was the system working as designed.

And it raises a simple question: if Britain needed gas last winter when the wind dropped, why would that reality disappear in future winters?

🔌 Electrifying Heat Raises the Risk

Policy assumes that gas heating can be replaced with electricity.

But last winter exposes the contradiction. When wind output fell, gas was required just to keep the electricity system running. Removing gas heating would shift millions of homes onto that same system during the coldest, stillest periods of the year.

Electrifying heat does not remove demand. It concentrates it at precisely the moments when supply is weakest. That increases risk — it does not reduce it.

📉 From Self-Sufficient to Import-Dependent

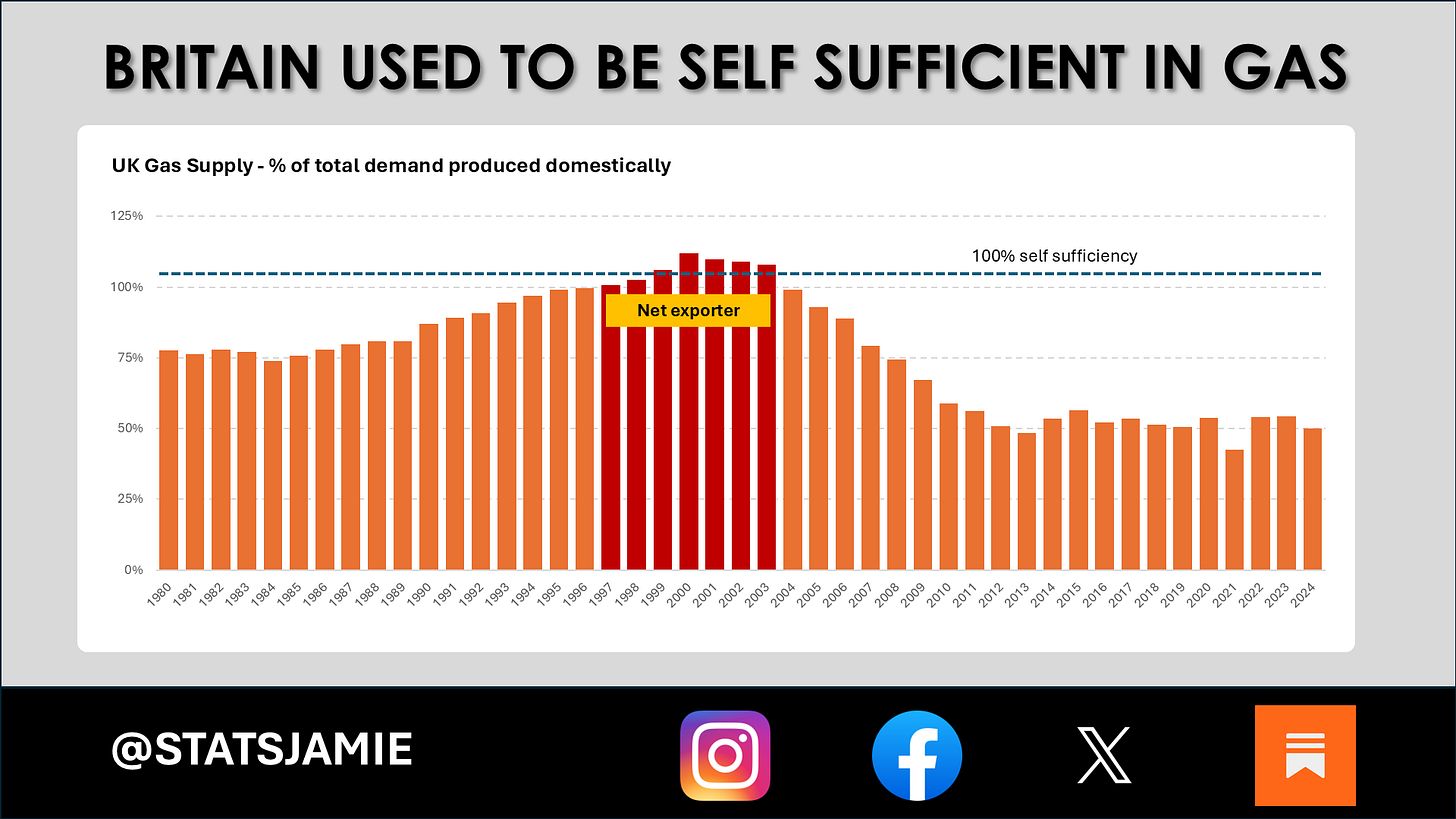

Britain once produced most of the gas it used. In the 1980s and 1990s, domestic supply comfortably met demand, and by the late 1990s and early 2000s, the UK was even a net exporter, producing more gas than it consumed.

Over time, that position reversed. As North Sea fields matured and fewer new ones were brought online, domestic production declined — slowly at first, then more sharply. The UK moved from producing almost all of its own gas to importing around half of what it uses today.

That dependence is most acute in winter, when gas demand peaks. Last year, in Q1 2025 (January to March), covering the core winter period, domestic production met just 35% of the UK’s gas demand, leaving the majority dependent on imports at the coldest time of year. That has not always been the case. During the winters of 1998 to 2001, domestic production consistently met around 97% of demand, providing far greater resilience during periods of peak consumption.

Overall gas demand has indeed fallen as other sources have been added to the energy mix, particularly for electricity generation. But that reduction has limits. From a heating perspective, gas remains critical. The majority of British homes still rely on it to stay warm in winter, and no alternative can deliver the same level of heat, instantly and at scale, during cold snaps.

The key point is simple: Britain has not transitioned away from gas. It has transitioned from producing gas at home to buying it from abroad.

🛢️ A Managed Decline, Not a Geological One

Around three-quarters of the UK’s gas imports now come from Norway, extracted from the same geological basin as Britain’s own North Sea reserves. The difference is not physical. It is political. Britain restricts new domestic production while importing the same fuel from next door, increasing exposure to international markets without reducing demand.

Ministers often describe falling North Sea output as “natural decline.” The industry argues the pace of that decline is a policy choice, not a geological inevitability. A 78% tax rate, combined with a ban on new exploration licences, has driven away an estimated £50 billion of investment that could have slowed the fall in domestic production.

The government’s own analysis acknowledges that around 70,000 jobs have already been lost across the offshore oil and gas sector. Meeting unchanged demand through imports does not reverse that loss — it exports production, investment and skilled work abroad, weakening the UK economy while leaving households just as reliant on gas as before.

🔥 If Not Gas, Then What Heats Homes?

If gas is removed from home heating, there are only a limited number of alternatives. The government’s preferred solution is to shift households onto electric heat pumps, replacing gas boilers with systems that run entirely on electricity.

On paper, heat pumps can be efficient in mild conditions. In practice, their performance deteriorates as temperatures fall. During the coldest periods — exactly when heating demand is highest — heat pumps work harder, draw more electricity, and deliver less heat per unit of power. That is not a design flaw. It is a physical limitation.

The problem doesn’t stop there. Heat pumps do not eliminate energy demand — they move it onto the electricity system. Millions of homes switching from gas to electric heating would sharply increase winter electricity demand, concentrating it into the coldest, stillest days of the year.

So the question becomes unavoidable: where does that electricity come from when the wind isn’t blowing, and it’s dark? Last winter provided the answer. When wind output fell, gas-fired power stations stepped in to keep the system running.

This exposes a fundamental flaw in the government’s thinking: removing gas from heating assumes an electricity system that does not yet exist, and ignores how the system actually behaves under winter stress.

🧍♂️ Cold Homes Have Consequences

This is not an abstract debate. Excess winter deaths rise when temperatures fall. Cold homes increase the risk of respiratory and cardiovascular illness, particularly among the elderly and vulnerable.

Heating is not optional infrastructure. Last winter showed what happens when the wind drops. This winter is showing it again.

Wind power has a role. Nuclear has a role. But when Britain is cold and calm, gas keeps people warm. Ignoring that reality and banning gas exploration does not make Britain greener — it increases reliance on imports and leaves the country poorer, weaker, and potentially colder.

✍️ Jamie Jenkins

Stats Jamie | Stats, Facts & Opinions

📢 Call to Action

If this helped cut through the noise, share it and subscribe for free — get the stats before the spin, straight to your inbox (no algorithms).

📚 If you found this useful, you might also want to read:

📲 Follow me here for more daily updates:

Thanks for an interesting article. I keep having this argument with my son in law who is fully on board with "The energy transition". He keeps telling me that we have this enormous installed capacity in renewables and I keep telling him that it doesn't matter how much installed capacity we have, at night when the wind is not blowing there is little electricity being generated from renewables. His answer is ah yes but we have battery backup and I have to explain that backup for renewables is gas not batteries. He thinks that if only we could get rid of all gas then electricity would be much cheaper. What can you do?

Excellent article, thank you. Regretfully, I believe the Government do not care how many frail, vulnerable people die as a result of the cold. Indeed, they probably welcome it.