China Added Four UKs’ Worth of CO₂ in Four Years — So What Is Britain Achieving?

Starmer wants closer ties with China — but Britain’s net-zero path and decades of offshoring have already boosted China’s economy while weakening our own.

Keir Starmer was in China last week talking about “deepening economic ties”. But there’s a brutal irony here. For decades, Britain has shifted manufacturing abroad — and a chunk of our emissions story has moved with it. Now we’re pursuing net zero in a way that raises costs at home, while relying heavily on imported kit often made in… China.

And if you want a reality check on the net-zero debate, don’t start with the UK. Start with what’s happened in China recently.

🌍 China’s emissions expansion — and the “9-day” punchline

One of the easy criticisms people throw back is: “China is bigger, so of course it emits more.” Fine. But the real story isn’t just the level — it’s the trajectory.

In just the four years from 2020 to 2024, China increased its annual CO₂ emissions by around 1.4 billion tonnes. That’s the equivalent of adding more than four UKs to the global total in one parliamentary term.

That one fact should reset the entire argument. Because it means Britain can spend years squeezing households and businesses to shave emissions down at the margin — and China can add multiple UKs worth of emissions in the time it takes Westminster to publish a strategy paper.

And then comes the kicker. In 2024, the UK emitted roughly 313 million tonnes of CO₂. China emitted around 12.3 billion tonnes. At that level, China emits the UK’s entire annual CO₂ in about nine days — and in a single year, China emits roughly 39 UKs worth of CO₂.

So when Westminster talks about net zero, the public is entitled to ask: what does this actually mean for Britain in day-to-day terms — especially when the global emissions dial is being turned elsewhere at a scale that dwarfs us?

⚖️ What net zero means — and who put it there

Net zero isn’t a slogan. It’s an accounting framework: the UK must cut greenhouse gases across the economy and then balance whatever remains with removals so the net total reaches zero. That’s why net zero doesn’t stay in one policy lane — it spreads into energy, transport, housing, farming, planning, and industry.

It’s also worth reminding people how we got here. The legal framework behind all of this was built in two stages. Labour passed the Climate Change Act in 2008, creating the carbon-budget machinery. Then, a decade later, it was the Conservatives under Theresa May who put net zero by 2050 into law in 2019 by tightening the long-term target to a full net-zero commitment.

Whatever your view on the goal, it has real-world consequences — and those consequences are not evenly shared. Households feel it through bills and mandates. Businesses feel it through competitiveness and investment decisions. Whole sectors feel it through what is encouraged, restricted, subsidised, or priced out.

🚢 Offshoring: importing emissions — exporting prosperity

A predictable rebuttal to the UK-versus-China scale point is: “Yes, but the UK has already cut loads.” True — but some of that story is not clean decarbonisation. It’s offshoring.

If you stop making things in Britain and import them instead, territorial emissions can fall — while the emissions still occur elsewhere in the supply chain. That doesn’t make the planet cleaner. It just changes which ledger the emissions sit on.

And this is where the trade-adjusted numbers matter. The consumption-based figures show the offshoring story in one glance. In 2023, the UK’s consumption footprint was 58% higher than its territorial emissions, while China’s consumption footprint was about 11% lower than the emissions it produces, because it exports so much manufactured output. In other words: Britain imports emissions; China exports them — and captures the jobs and industrial base that come with it. (Consumption-based emissions typically run about a year behind territorial totals because they depend on detailed international trade data.)

This is the economic side of “exported emissions”. When a country increasingly uses wealth created at home to buy goods made abroad, that wealth doesn’t circulate domestically. It leaks out — along with jobs, investment, and the tax base. Over time, the country becomes poorer, less resilient, less productive, and more dependent.

Net zero risks accelerating that pattern if it pushes up the cost of producing in the UK while we import more of what we consume — including the hardware used for the transition itself.

⚡ Competitiveness: the energy-cost trap

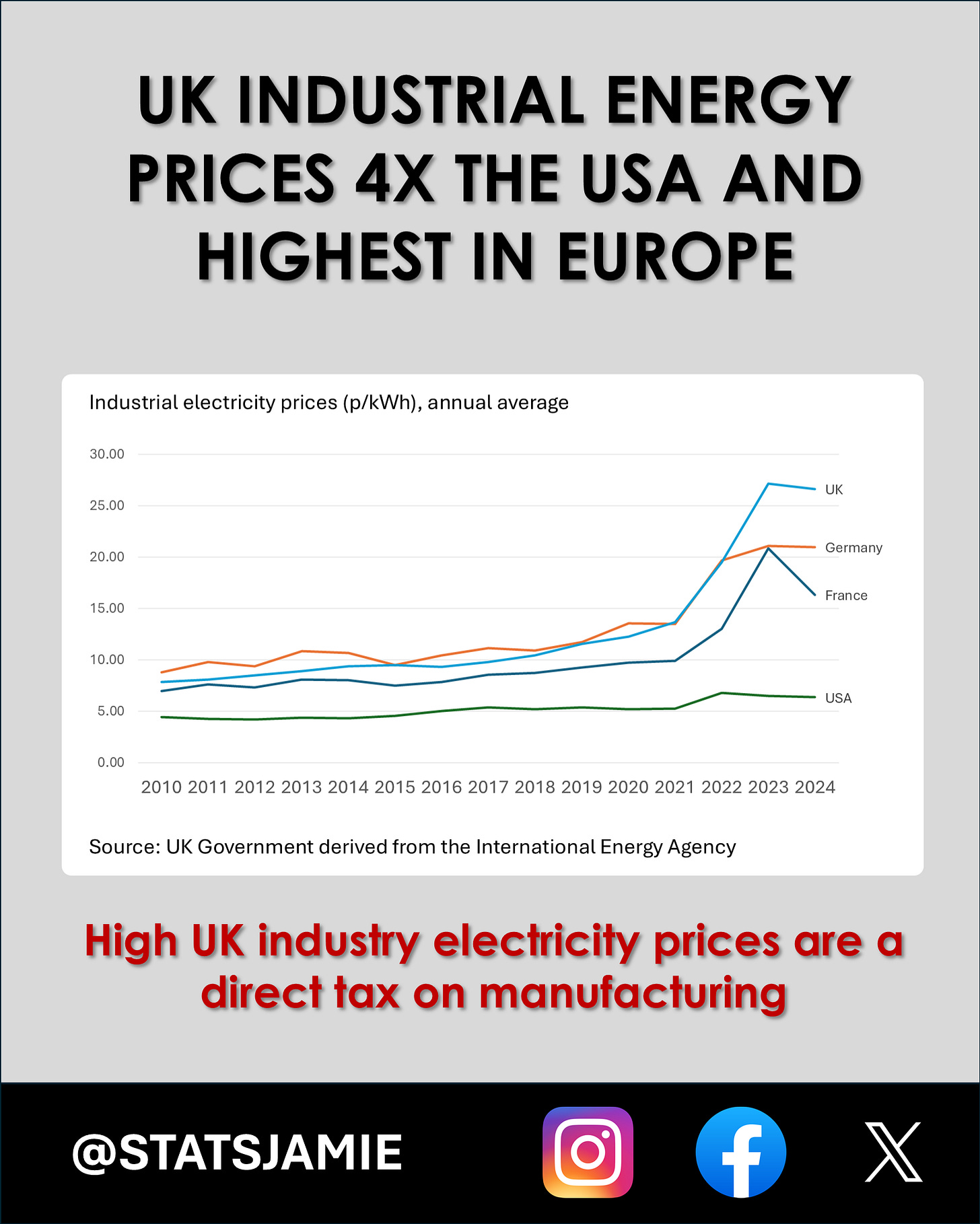

If you want to see why industry keeps leaving, start with electricity. The chart below shows UK industrial power prices miles above competitors — especially the US — and that gap is a direct tax on making things in Britain.

If industrial electricity prices sit far above those of competitor nations, you are effectively loading extra cost onto every unit of output. Manufacturers either absorb it (and invest less), pass it on (and raise prices), or move (and take jobs with them). That’s not ideology — it’s basic economics.

And it isn’t just the US the UK competes with. China’s industrial power pricing varies by region, but the direction is clear: in many areas it is materially cheaper than the UK — and in some cases cheaper than the US as well. So offshoring isn’t only about labour anymore — it’s about input costs, with energy increasingly central.

When politicians promise that net zero will deliver a new industrial future, the obvious question is: where is that industry meant to operate if electricity is priced like a luxury good?

🏗️ The green supply chain irony — and the leak in the system

There’s another irony that’s becoming harder to ignore. Britain is told net zero will build green jobs and green industry — yet much of the kit underpinning the transition is imported, frequently from China. So the “transition” can become a model where Britain absorbs higher domestic costs while much of the manufacturing value-add accrues overseas.

Put all of this together, and the uncomfortable picture sharpens. Starmer talks about deepening economic ties with China. But Britain has already deepened dependence through decades of offshoring — and net zero risks tightening the vice by making UK production less competitive, while the global emissions trajectory is still driven by China at a scale that dwarfs the UK.

✅ A grown-up discussion Britain isn’t having

The uncomfortable truth is that Britain is being asked to absorb real economic costs in the name of a domestic emissions target — while the global emissions trajectory is driven by countries operating at vastly greater scale. China can match a UK-year of CO₂ in around nine days, and it has added multiple “UKs” worth of emissions in just the last few years.

Yet instead of an honest national conversation, we get politics-by-slogan.

The Conservatives embedded net zero into law. Labour has doubled down and put figures like Ed Miliband front and centre, treating a “build more wind” agenda as a substitute for an industrial strategy. Meanwhile, households and businesses are left paying the bill through high energy costs, creeping restrictions, and policies that make it harder to produce competitively in the UK.

Britain doesn’t need a climate policy built on vibes, guilt, and ever-higher domestic costs. It needs a grown-up approach that starts with scale, confronts offshoring, and puts prosperity and resilience at the forefront of government policy.

Because if net zero becomes a project that weakens the productive base of the UK while strengthening the world’s dominant manufacturing power, it won’t be remembered as leadership.

It will be remembered as national decline by design.

✍️ Jamie Jenkins

Stats Jamie | Stats, Facts & Opinions

📢 Call to Action

If this helped cut through the noise, share it and subscribe free by entering your email in the box below and get the stats before the spin, straight to your inbox (no algorithms).

📚 If you found this useful, you might also want to read:

Ed Miliband vs Winter: When Net Zero Meets Cold Reality

·

8 Jan

📲 Follow me here for more daily updates:

It’s achieving net zero growth whilst enriching the Chinese. We are commiting economic suicide and paying for the privilege…