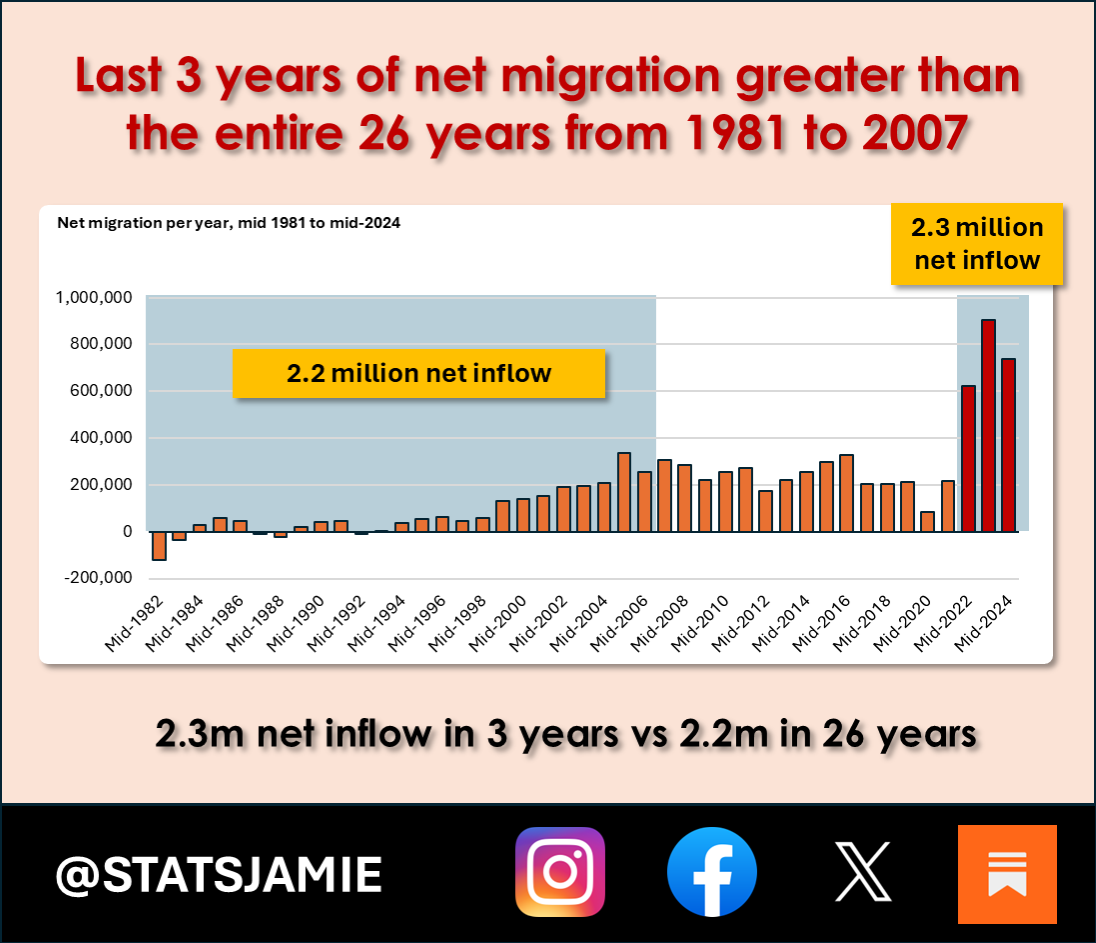

Last 3 Years of Net Migration Outstrip the Entire 26 Years from 1981–2007

2.3 million net inflow since 2021 – outstripping the 2.2 million seen from 1981 to 2007.

The Office for National Statistics released its mid-2024 population estimates last week. The headline numbers tell a story we’ve never seen before in modern Britain.

In the last three years — between mid-2021 and mid-2024 — net migration added 2.3 million people to the UK population. Over the same period, there were around 2.017 million births and 1.982 million deaths, leaving a natural increase of just 34,000. That means 98.5% of the UK’s population growth in the last three years has come from immigration.

To put that in perspective: from 1981 to 2007 — a span of 26 years — net migration added 2.2 million people in total. In other words, what once took over a quarter of a century has happened in the last three years.

How It Used to Be

In the 1980s and early 1990s, population growth primarily resulted from natural change — an increase in births over deaths. Net migration was modest, typically in the tens of thousands each year, and in four years it was negative, with more people leaving than arriving.

Growth in that period was steady and predictable, giving time for housing, schools and services to expand gradually.

The Post-1998 Explosion

The shift came in the late 1990s.

Between mid-1998 and mid-1999, net migration passed 100,000, hitting 133 thousand. From there, it climbed steadily. During the Blair years, migration became the dominant driver of population growth.

This continued under the Cameron and May governments, with annual inflows regularly running at 200,000–300,000.

Then came the pandemic. In the first Covid year, net migration dropped to just 84,000. But as restrictions lifted, the numbers didn’t just bounce back — they exploded under Boris Johnson:

624,000 in the year to mid-2022

906,000 in the year to mid-2023

739,000 in the year to mid-2024

These are levels Britain has never seen before.

The Housing Crunch

This demographic surge has collided with a housing market already failing to keep up with demand.

Take England and Wales as an example:

In 1998, just before the migration surge, the average house price was £60,000. The average annual wage was £17,631. That’s a ratio of 3.4 times salary.

By 2024, the average house price had risen to £280,000 — a 367% increase. Wages, by contrast, rose only 113% to £37,468.

The house price-to-earnings ratio has more than doubled to 7.5.

The ratio actually peaked at 8.8 in mid-2021, but higher interest rates and weaker economic conditions have cooled prices slightly. Even so, affordability remains at crisis levels.

The Consequences

Young adults: Many can’t afford to move out unless cohabiting, delaying independence and family formation.

Falling fertility: Birth rates are now at their lowest for over 40 years, partly because high housing costs discourage family starts.

Vicious cycle: Lower birth rates then become the justification for further immigration to fill workforce gaps, which piles more pressure on housing and services.

Public services: Natural change is gradual and predictable. Migration surges are sudden. Too many people chasing too few homes, GP appointments, school places and hospital beds.

The Cultural Dimension

It isn’t just the size of the flows that matters, but also their character.

Most of the record net migration in the last three years has come from non-EU countries. The top five countries of origin have been India, Nigeria, Pakistan, China and Zimbabwe.

This represents a profound cultural shift. Britain has always been shaped by immigration, but never at this pace or scale. Communities are being reshaped within a single generation, not across several. That brings both opportunities and challenges — for integration, social cohesion, and the sense of national identity.

A Generational Shift

Older generations remember when population growth was slow, steady and home-grown. Today, almost all of it is immigration-driven. And the pace — the last three years equalling 26 years — is unprecedented.

This is not just a demographic footnote. It is a transformation reshaping Britain’s housing market, its public services, and its cultural fabric.

Final Thought

In the last three years, net migration has exceeded the entire inflow of the 26 years between 1981 and 2007.

Coupled with a housing market where prices have risen more than three times faster than wages, and with migration flows now predominantly from non-EU countries, the impact on affordability, services, and social cohesion is profound.

This is not gradual, generational change. It is a demographic shift happening at speed — one Britain’s leaders have failed to prepare for.

✍️ Jamie Jenkins

Thanks for reading Stat of the Nation. If you find these stats and insights useful, please share or subscribe to support my analysis.

I crunch the numbers so you don’t have to.

📲 Follow me here for more daily updates:

"Britain has always been shaped by immigration, but never at this pace or scale."

Has it? Really? I don't think a few Hugenots shaped very much. Post war Britain has seen immigration that has been changing things but my grandmother (born 1893, died 1975) grew up in a pretty unchanged world of white natives who generally didn't move more than a few miles and married locally. My father grew up in Plumstead in south London (his parents lived in south London from the time of the first war until they died) - it was 100% white natives, most of whom had been there for generations. I doubt there are more than a handful of locals still living in Plumstead now - it appears to be mostly immigrants from the sub-continent who haven't even tried to assimilate. So, I would disagree that Britain has always been shaped by immigration - it has simply been flooded with immigrants since the 1950s at an ever increasing rate and those immigrants have no real need or desire to become British so have turned whole areas into ghettos or enclaves. South London has very few areas left where native populations are the majority - this is not progress but simply destruction.