85,000 Under-25 Payroll Jobs Gone — Youth Hit Hardest Since the Election

UK youth unemployment has now moved above the EU average — while Germany and Japan show what a working pipeline looks like.

Over the past week, more commentators have started to notice a familiar problem: youth unemployment is rising, and young people are struggling to get a foothold in the labour market.

But this isn’t new to readers of Stat of the Nation. I’ve been highlighting for months that when the jobs market weakens, young people get hit first.

Now the latest data is in — and it’s ugly. Since June 2024 (pre-election baseline), the UK has lost 161,928 payrolled employee jobs. And 85,440 of those losses are people aged under 25 — over half the total fall.

That’s the big picture: the jobs market is weakening, and the pain is landing hardest at the bottom rung.

💷 Payroll Data First: The Most Robust Jobs Signal Says We’re Going Backwards

Let’s start with the cleanest dataset: PAYE Real Time Information (RTI) from HM Revenue & Customs.

This is not a survey. It’s based on employer payroll records, which makes it the most reliable way to track recent changes in jobs.

Compared with June 2024, by January 2026:

Total payrolled employee jobs: -161,928

Under-25 payrolled employee jobs: -85,440 (around 53% of the total fall)

When over half of the total decline sits in the youngest bracket, it tells you exactly where the weakness is concentrated: entry-level work and early-career jobs.

And that’s the point: this isn’t “some people struggling”. It’s the labour market ladder getting pulled up.

🧾 The People Behind the Numbers: What the Labour Force Survey Shows

To understand what’s happening to young people in more detail, we turn to the Labour Force Survey from the Office for National Statistics.

By its nature, it’s a survey — so it’s more prone to sampling variability and non-response issues than payroll data. That’s why PAYE is the best “recent change” indicator.

But the survey gives us something payroll can’t: a breakdown of young people into work, unemployment, education, and inactivity.

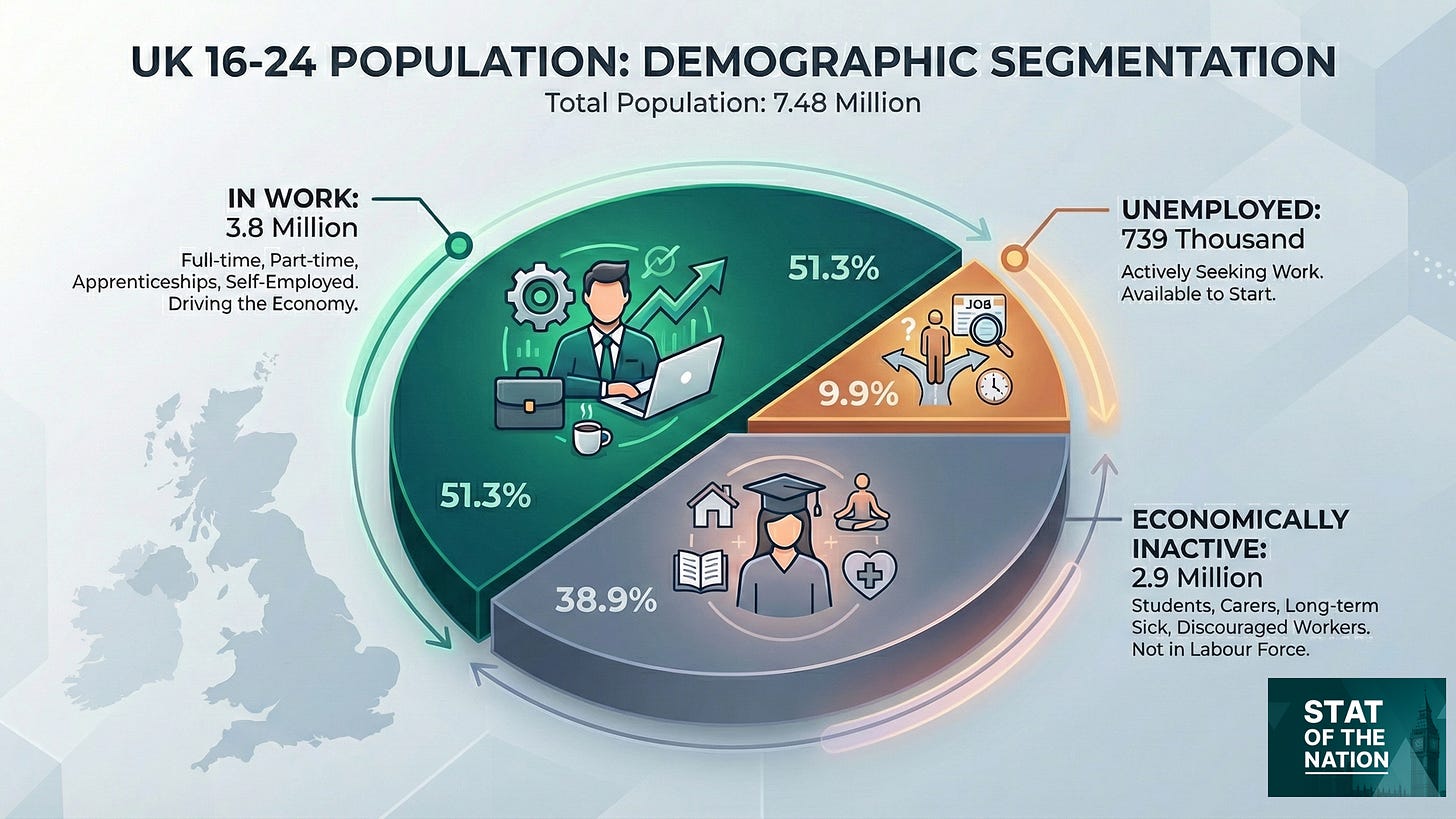

Latest snapshot (ages 16–24, Oct–Dec 2025):

Total 16–24 population: 7.48m

In work: 3.8m (51%)

Unemployed: 739k (10%)

Economically inactive: 2.91m (39%)

Here’s the key clarification most commentary gets wrong:

Roughly 1 in 10 young people (16–24) are unemployed, but the headline unemployment rate that gets quoted is 16.1%. That’s because the unemployment rate is calculated as unemployed ÷ (employed + unemployed) — in other words, it measures unemployment only among those who are active in the labour market, not all young people.

What’s changed since just before the election

If we compare Apr–Jun 2024 (pre-election) to Oct–Dec 2025:

Youth unemployment rate: 13.4% → 16.1% (+2.7pp)

Unemployed young people: 575k → 739k (+164k)

And the split matters. Of the 739k unemployed:

270k are unemployed, in full-time education (job-search alongside study)

469k are unemployed, not in full-time education

That second figure is the bigger warning light: nearly half a million young people not in full-time education want a job and can’t get one.

In addition to those who are unemployed, there’s another group that matters just as much: young people who aren’t looking for work at all — classed as economically inactive.

If we focus on those not in full-time education, the latest Labour Force Survey shows 793,000 young people aged 16–24 are inactive and not in full-time study. This may include some people in part-time education or training, but the headline is still stark. Add that 793,000 to the 469,000 young people who are unemployed and not in full-time education, and you get around 1.3 million young people who are disconnected from work outside full-time study — at a time when benefit dependence is growing in this age group.

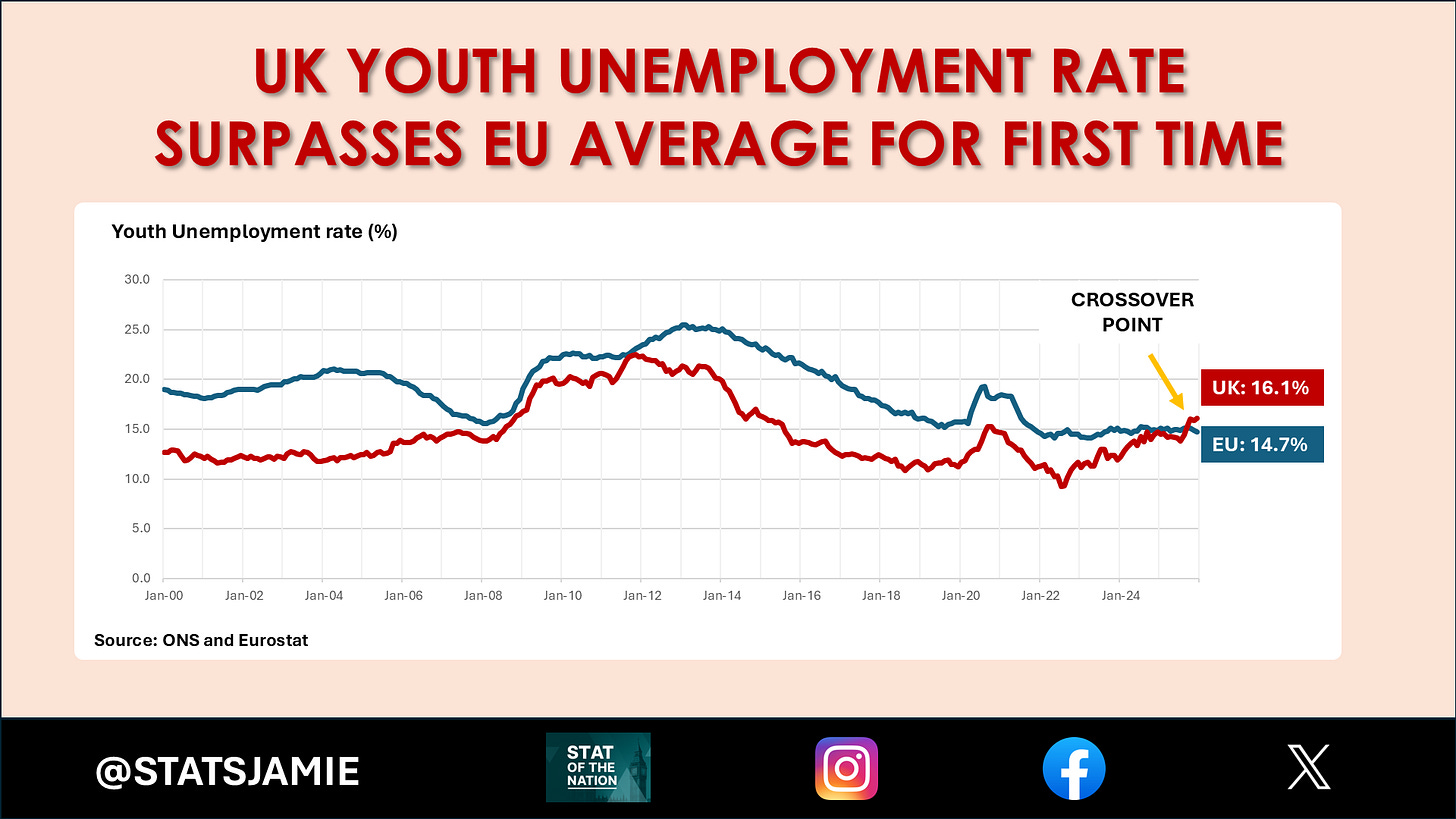

🌍 UK vs Europe vs the World: Youth Unemployment Has Overtaken the EU Average

So how does the UK compare with the rest of the world?

If we start with the UK versus the European Union, the picture is telling. For most of the period since records began, the UK has typically run a lower youth unemployment rate than the EU average. But that relationship has flipped in recent months — the UK has now overtaken the EU average, meaning our youth jobs market has moved from “better than Europe” to worse than the European benchmark.

Using the closest comparable month alignment, UK youth unemployment moved above the EU average in September 2025, and by December 2025, the UK was about 1.4 percentage points above the EU average.

That matters because the EU has long struggled with youth unemployment — the UK drifting above it is a warning sign in itself.

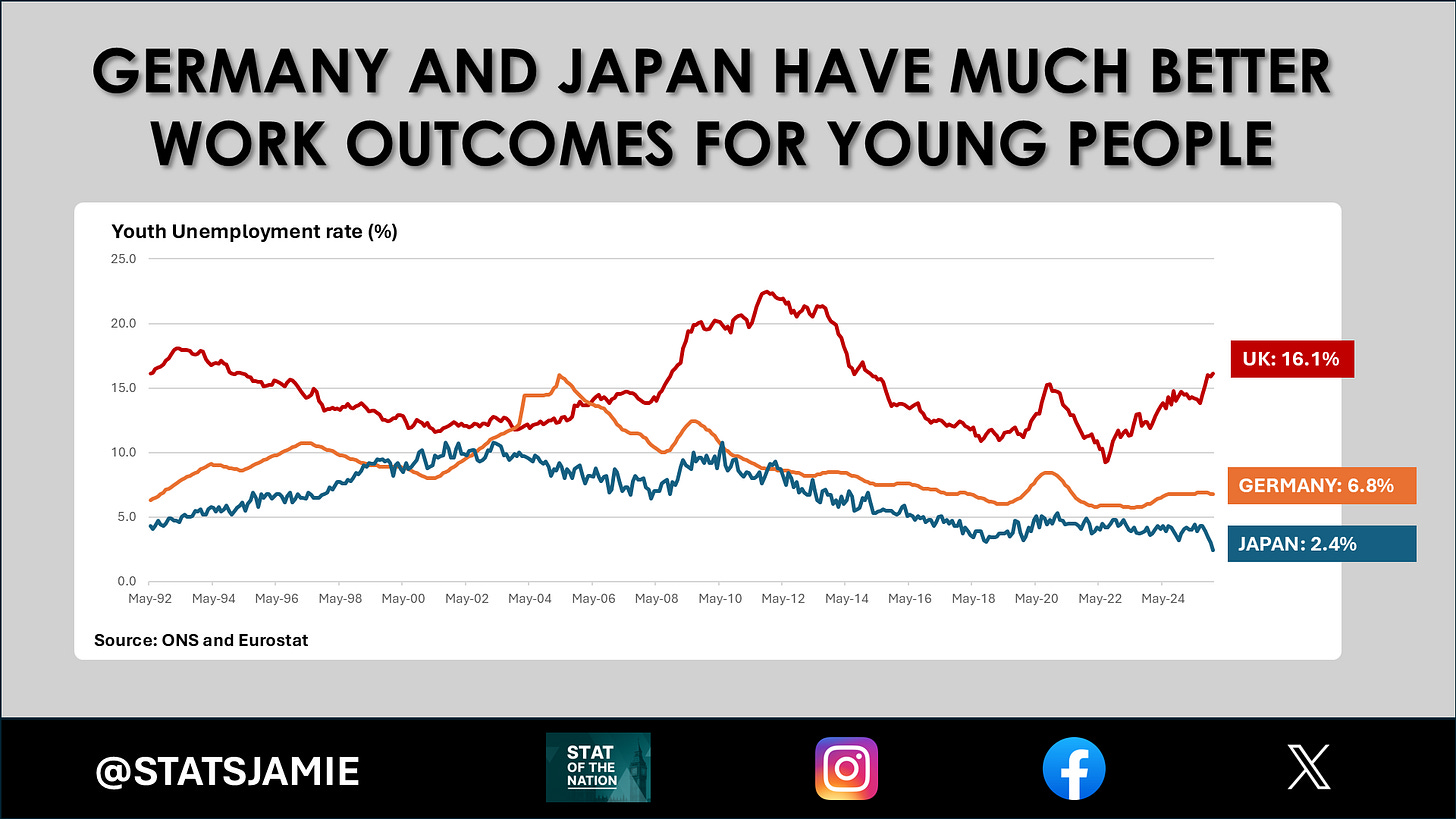

🌍 Germany and Japan Show What a Working Youth Jobs System Looks Like

Apart from a period in the mid-2000s, Germany has consistently run a lower youth unemployment rate than the UK, and Japan is lower still. So this isn’t a one-off good year for them. It’s a sustained pattern: their systems are simply better at getting young people onto the first rung of the jobs ladder.

That matters, because it tells us the UK’s problem isn’t “bad luck”. It’s structural. And if we want to fix it, we need to be honest about what the best performers are doing differently.

🏭 What Germany does (in practical terms)

Germany’s big advantage is that it doesn’t treat education and employment as two separate worlds. It runs a mainstream vocational pipeline where a large share of young people move into paid apprenticeships that are directly linked to employers. The key is that this isn’t a second-best option — it’s a respected route into skilled work, with real progression.

Crucially, employers aren’t passive. They’re directly involved in training because the system is built around what firms actually need — and because qualifications are standardised and valued, young people leave with skills that translate straight into jobs. The result is fewer young people stuck in the UK-style limbo of “get a degree, then compete blind for entry-level roles with no experience.”

🏢 What Japan does (in practical terms)

Japan achieves even lower youth unemployment through a more structured transition into first jobs. Hiring is organised around clear recruitment cycles — particularly for new graduates — and the path from education into work is more coordinated. The point isn’t that Japan has a magic wand; it’s that the system is designed so that most young people don’t spend long periods floating between education and unemployment.

It’s also a culture where missing that first step can carry a cost — but the flip side is that the system places a much stronger emphasis on getting young people into work early, quickly, and in a way that builds stability rather than churn.

Put simply, Germany builds a pipeline through paid vocational training. Japan builds a pipeline through structured entry into first jobs. And both systems mean far fewer young people are left disconnected from work outside full-time study.

🏛️ Britain Is Broken — and Young People Are Paying the Price

⚠️ The short-term shock: higher hiring costs in a weak economy

The jobs market is already fragile — and government policy has made it worse. Employers have faced changes to when National Insurance starts being paid, plus higher National Insurance contributions — effectively a jobs tax that raises the cost of taking someone on. At the same time, the national minimum wage for young people has risen sharply, in some cases faster than adult rates. That sounds compassionate, but when budgets are tight, it can reduce the incentive to hire and train inexperienced workers — and entry-level roles are always the first to go when confidence drops.

As I’ve written before, the government’s response looks like a sticking plaster. Since June 2024, the PAYE payroll data shows around 85,000 payrolled jobs have been lost among the under-25s, and the answer from Westminster is to spend £1.5bn trying to “create” 50,000 apprenticeships. Even if every place materialises, it’s a costly scheme that doesn’t come close to filling the hole that’s already opened up for young people.

🧱 The long-term failure: an education system not joined up to work

But this isn’t just cyclical, it’s structural. For years, Britain has pushed ever more young people into university — accelerated under Tony Blair — with the promise it would open doors. Too often, the result is large debts and no guarantee of work, especially where degrees don’t match what employers actually need. We’ve built an education pipeline that isn’t properly linked to the jobs market — and successive governments have failed to fix it.

That’s why the Germany and Japan comparison matters. Their systems don’t leave young people to “figure it out” after education — they connect training to real jobs. Britain doesn’t. And the result is perverse: politicians then say we “need immigration” to fill roles, while huge numbers of young people sit unemployed, inactive, or outside work and full-time study — young people who could be trained up to do these jobs if the system actually worked.

✍️ Jamie Jenkins

Stats Jamie | Stats, Facts & Opinions

📢 Call to Action

If this helped cut through the noise, share it and subscribe free by entering your email in the box below and get the stats before the spin, straight to your inbox (no algorithms).

📚 If you found this useful, you might also want to read:

📲 Follow me here for more daily updates:

Previous govts insisting all kids should stay at school until they're 18 and then all kids should go to university served two purposes. It kept 16 to 21 year olds off unemployment lists and it gave a balm to the class warriors who thought only toffs went to university. Getting rid of useful polytechnics which taught trades was a huge mistake. Telling working class kids that going to a newly invented third rate university to study law would turn them into something out of an Evelyn Waugh book was a huge lie. Kids wasting years and pounds getting a useless degree from London Metropolitan university and then discovering Mischon de Reya only takes Oxbridge graduates whose parents are partners. I knew old blokes who had left school at 14, gone into a poorly-paid 7-year apprenticeship and come out with a life-long skill. The govts all in turn destroyed that system which had existed for centuries. I know a young woman who has amassed a load of debt getting a degree in weaving - took her 3 years and obviously she can't get a job as a weaver because it's a hobby that might make you a few bob selling in craft markets. Education in this country is full of class hatred - get rid of grammar schools because only posh people are clever, get rid of polytechnics because it's not fair only posh people go to university, get rid of apprenticeships because posh people don't do them. I have a daughter with 3 degrees and a daughter with a Cordon Bleu cookery diploma. One has a job which is basically a secretary/office manager. One runs a small baby food business.

Great segment on Mike Graham's show today Jamie.

I went to University when only 5% of school leavers went to University and overall unemployment was just 3.5 % !